|

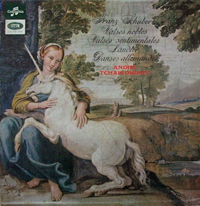

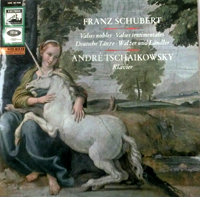

Cover for

EMI Columbia

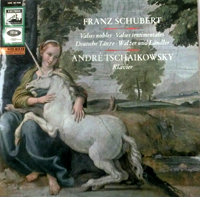

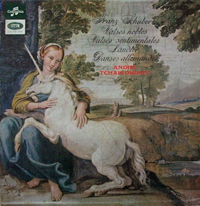

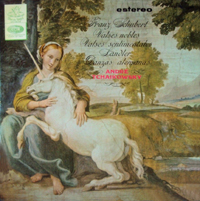

Cover for

EMI Electrola

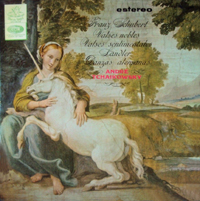

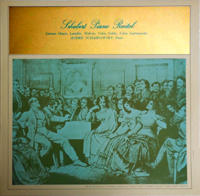

Cover for

Discos Angel

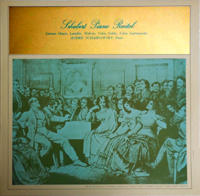

Cover for World Record Club

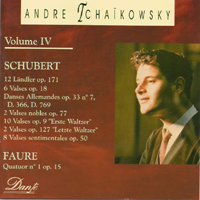

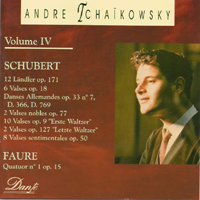

Cover for Danté Reissue

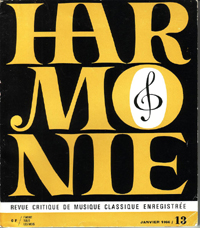

Harmonie

Magazine Review

January 1966

Click Here - in

French

Click

Here - in English

Click

Here - Bnf Reference

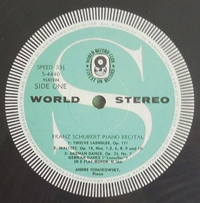

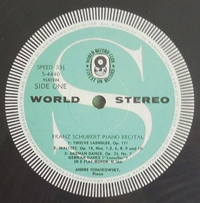

Test pressing

YLX1204/YLX1205

World Record Club Disc

|

Columbia

Records (EMI Pathé Marconi) SAXF-1057 (Stereo) (French)

Columbia Records (EMI Pathé Marconi) FCX-1057 (Mono) (French)

Columbia Records (EMI Electrola) SME-80988 (Stereo) (German)

Discos Angel SLPC-12256 (Spanish)

World Record Club WRC-S-1440 (Australia)

Reissue - Danté Records, HPC049 - Vol. 4

Schubert Recital

Music/MP3

Schubert -12 Ländler, Opus 171

1. Opus

171, No. 1 / 01_schubert_opus_171_no_1.mp3

2. Opus 171, No. 2 / 02_schubert_opus_171_no_2.mp3

3. Opus 171, No. 3 / 03_schubert_opus_171_no_3.mp3

4. Opus 171, No. 4 / 04_schubert_opus_171_no_4.mp3

5. Opus 171, No. 5 / 05_schubert_opus_171_no_5.mp3

6. Opus 171, No. 6 / 06_schubert_opus_171_no_6.mp3

7. Opus 171, No. 7 / 07_schubert_opus_171_no_7.mp3

8. Opus 171, No. 8 / 08_schubert_opus_171_no_8.mp3

9. Opus 171, No. 9 / 09_schubert_opus_171_no_9.mp3

10. Opus 171, No. 10 / 10_schubert_opus_171_no_10.mp3

11. Opus 171, No. 11 / 11_schubert_opus_171_no_11.mp3

12. Opus 171, No. 12 / 12_schubert_opus_171_no_12.mp3

Schubert - Valses, Opus 18, No. 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 10

1. Opus

18, No. 1 / 13_schubert_opus_18_no_1.mp3

2. Opus 18, No. 2 / 14_schubert_opus_18_no_2.mp3

3. Opus 18, No. 6 / 15_schubert_opus_18_no_6.mp3

4. Opus 18, No. 8 / 16_schubert_opus_18_no_8.mp3

5. Opus 18, No. 9 / 17_schubert_opus_18_no_9.mp3

6. Opus 18, No. 10 / 18_schubert_opus_18_no_10.mp3

Schubert - Dances allemandes, Opus 33, No. 7

Danse Op.

33, No. 7, D783 / 19_schubert_opus_33_no_7.mp3

Schubert - "Ländler" en mib mineur, D. 366

Danse D366

/ 20_schubert_danse_d_366.mp3

Schubert - Deux danses allemandes, D. 769

1. Danse

No. 1, D769 / 21_schubert_danse_no_1_d_769.mp3

2. Danse No. 2, D769 / 22_schubert_danse_no_2_d_769.mp3

Schubert - Valses nobles, Opus 77, No. 9, 10

1. Opus

77, No. 9 / 23_schubert_valses_nobles_opus_77_no_9.mp3

2. Opus 77, No. 10 / 24_schubert_valses_nobles_opus_77_no_10.mp3

Schubert - Valses, Op 9, No 19, 21, 22, 26, 29, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36

1. Opus

9, No. 19 / 25_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_19.mp3

2. Opus 9, No. 21 / 26_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_21.mp3

3. Opus 9, No. 22 / 27_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_22.mp3

4. Opus 9, No. 26 / 28_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_26.mp3

5. Opus 9, No. 29 / 29_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_29.mp3

6. Opus 9, No. 30 / 30_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_30.mp3

7. Opus 9, No. 32 / 31_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_32.mp3

8. Opus 9, No. 34 / 32_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_34.mp3

9. Opus 9, No. 35 / 33_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_35.mp3

10. Opus 9, No. 36 / 34_schubert_valses_opus_9_no_36.mp3

Schubert - "Letzte Walzer" Opus 127, No. 15, 18

1. Opus

127 / No. 15 / 35_schubert_valses_opus_127_no_15.mp3

2. Opus 127 / No. 18 / 36_schubert_valses_opus_127_no_18.mp3

Schubert - Valses sentimentales, Opus 50, No. 1, 3, 7, 12, 13, 15, 19,

27

1. Opus

50 / No. 1 / 37_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_1.mp3

2. Opus 50 / No. 19 / 38_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_19.mp3

3. Opus 50 / No. 27 / 39_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_27.mp3

4. Opus 50 / No. 3 / 40_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_3.mp3

5. Opus 50 / No. 7 / 41_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_7.mp3

6. Opus 50 / No. 15 / 42_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_15.mp3

7. Opus 50 / No. 12 / 43_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_12.mp3

8. Opus 50 / No. 13 / 44_schubert_valses_opus_50_no_13.mp3

Fauré [Danté reissue only] Quatuor No. 1, Op. 15

André

Tchaikowsky, piano

Michael Belmgrain, violin

Lars Grund, Viola

Ino Jansen, Cello

1. Allegro

molto moderato / 45_faure_quatuor_no_1_op_15

_1.mp3

2. Scherzo - Allegro vivo / 46_faure_quatuor_no_1_op_15

_2.mp3

3. Adagio / 47_faure_quatuor_no_1_op_15

_3.mp3

4. Allegro molto / 48_faure_quatuor_no_1_op_15

_4.mp3

Recording

Date(s):

Schubert

- April 14 to 16, and June 1, 1965

Fauré - c. 1972

Recording

Location:

Schubert - Salle Wagram, Paris, France

Fauré - Copenhagen, Denmark

Release

Date:

Schubert

- c. 1965

Fauré - 1996

Harmonie

Magazine Review (January 1966):

After Alain Motard, André Tchaikowsky invites us to a "Schubertiade",

a Schubert gathering, in a program that has very few overlaps with the

other one. I am possibly more satisfied with his interpretation, in

this specific repertoire; at the most, he can be faulted for sometimes

playing too much in the manner of Chopin a Waltz or two, that would

have accommodated simpler phrasings and rhythms. Petty detail, in view

of the fine sensibility, the tenderness and, when called for, the robust

and peasant-like verve that the artist brings to these marvellous little

masterpieces.

André

Tchaikowsky operates the most judicious distinction between the Waltzes,

Ländler and Allemandes in his program, which he alternates with

a commendable care for variety. But above all, his most laudable merit

is to return to this music its intimate and "hair-down" character.

He never seems to be playing for an audience or sound engineers. He

strings the pearls on his necklace of dances with an adorable air of

nonchalance, and beyond his undisputable qualities of color, rhythmic

life, finely nuanced expression, the dearest virtue of his interpretation

is its feeling of naturalness.

Harry

Halbreich (Trans. Edouard Reichenbach)

Known

Details:

There are no specific references to these recording sessions in

André's correspondence or other available documentation, but

it was just at this time that André got a new manager at his

London concert management agency, Ibbs and Tillett. From the book, The

Other Tchaikowsky - A Biographical Sketch of André Tchaikowsky:

Enter

the Hero (1965)

André's

concert manager at Ibbs and Tillett was getting a bit fed up with the

typical André antics, turning down concert dates, or insulting

someone at the concert dates that he did accept. He became one of their

problem artists. For two years, Mrs. Emmie Tillett had been refusing

employment to a young bank employee, Terence (Terry) Harrison, who wanted

to join her artist management company. In 1965, Terry got his chance.

Ibbs and Tillett hired him and gave Terry the "opportunity"

to manage a few of their "problem" artists. One of them was

André Tchaikowsky.

Terry Harrison

was a hero in the life of André Tchaikowsky, as he became in

the lives of a number of "difficult" artists. From 1965 to

the end of his life, André's career was managed by Terry Harrison,

without whom, in all probability, his career would have ended, with

grave personal consequences. Terry had a quality that all André's

previous artistic managers had considered unprofessional: he was able

on a sustained basis to be André's friend. Considering André's

personal behavior, this was no small thing. You had to be sensitive

to André's moods, which could change within hours; you had to

be comfortable with the fact that André would not always act

in his own best interests; and you had to accept André's failure

to keep appointments unless constantly cajoled. You also had to explain

André's often strange behavior to others, and smooth over hurt

feelings. Terry had the almost hopeless task of forging a career for

someone who badly needed, but didn't want, a career. On the other hand,

Terry had a brilliant artist to market if he could find a way to do

it.

Terry Harrison

and another young man at Ibbs and Tillett, Jasper Parrott, eventually

went on to form one of the greatest artistic management companies in

the world, Harrison/Parrott of London, and the reason for their success

was that they could combine good management with caring and affection

for their artists. Where some managers were quite willing to squeeze

musicians dry by overloading them with too many concerts, Harrison/Parrott

listened to what their artists wanted, and sought ways to achieve a

satisfactory path that was humane and rewarding, both artistically and

financially.

As his

manager, Terry set about to understand André. Where some saw

André as a tragic figure who could have had a large career like

Rubinstein's, Terry didn't see that at all. What Terry saw was a great

artist who was trying to fashion a career of his own imagination, trying

to be both a pianist and composer. He did not blame André for

being disturbed by a musical marketplace that judged success more on

what happened after a concert than what happened on stage. He read the

reviews of André's concerts and saw that they revealed the seriousness

of his intent, how he tried to "get inside" each composition

and tried to achieve a thoughtful elucidation instead of just pleasing

the crowd. He further saw that André regarded the role of star-status

musician -- for whom concerts were media events, jetting from one guest

appearance to another -- as anti-musical, and couldn't cope with it.

Terry Harrison

remembers his early days at Ibbs and Tillett:

"André

was difficult to manage in two or three ways. He was difficult in

that he was often a little bit complicated in his arrangements. It

could be simple: go, get on the train, do the concert, and come back

again. But André wasn't sure how he was going to go, then he

was going to meet this friend, or stop somewhere along the way so

he could eat a good meal, or that kind of thing.

"If

he had been a character that had not been so well liked, that would

have been a hassle. But one never really thought of it as a hassle

because André had a great ability to communicate with people

he liked and was full of charm. He was certainly one of the best-liked

artists in our agency. André was very simpatico, although at

times obsessed with his own problems. Usually when he met people,

he was not into his own problems and he gave you the feeling he was

interested in you and your problems, you know, 'How's your life?'

"There

were times when it was difficult to manage André in another

way. That was when he became obsessed by something like a person he

didn't like, a person connected with the concerts, or a conductor

he didn't like. It was very difficult sometimes, or he became obsessed

that he was falling behind with his composing, and would turn down

things. Sometimes I had to persuade him that he shouldn't turn down

these things, either because he needed the money, or because it was

an engagement that he should do because it was important. It often

took a long time to persuade him but usually I was successful. It

used to take two and three discussions over two or three days to get

through. I felt he went into a shell and cooled, but that didn't last.

"He

actually should have been busier and playing more concerts, but he

became more and more interested in his composing, so the time that

he would give us became more and more restricted for concerts. He

liked to do things for pleasure rather than prestige. He wasn't prestige

orientated and turned his back on the whole star system in the early

1960s when he could have probably done very well. He turned his back

on it because he felt it was, to some extent, anti-musical. He also

felt that you had to put on an act and a face and not be yourself.

He felt you couldn't be your own man in the star system. You had to

be someone who would perform in a certain fashion. He felt he was

first a musician and very, very secondarily, a performer. He thought

the star system had it the other way.

"He

was my closest friend, and since he died I certainly haven't found

a friendship like André's. He was really very, very special."

Here is

a brief mp3 audio clip from the BBC Radio 3 program about André

Tchaikowsky (A Study in Contrast), where Terry Harrison remembers André

(narrated by pianist David Owen Norris): contrast_terry.mp3

You can

find the entire program "A Study in Contrast" by clicking

the Miscellaneous button above.

|