|

Click

Here for a portion of the Study in Contrast radio program

discussing the piano concerto with David Owen Norris, Radu Lupu, and

John Schofield.

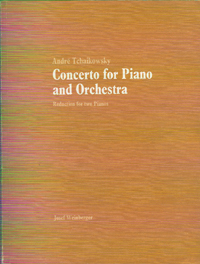

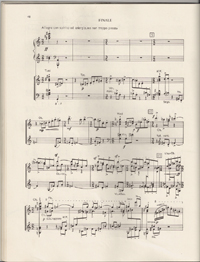

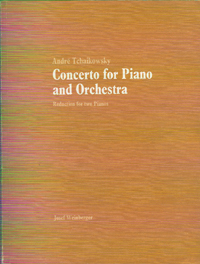

Reduction for Two Pianos

Introduction

Passacaglia

Capriccio

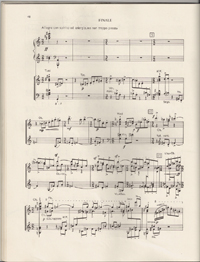

Finale

1st Page Original Manuscript

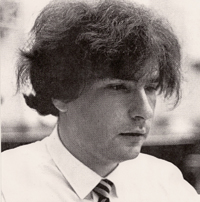

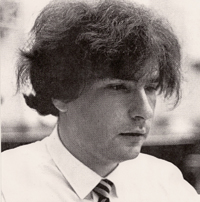

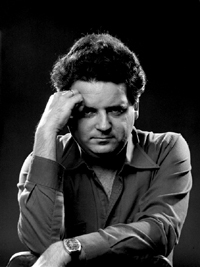

Radu Lupu (1972)

(1st performance)

Radu Lupu

(1975) with Elizabeth Wilson (L) and Judy Arnold (R)

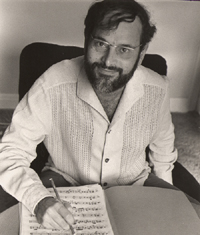

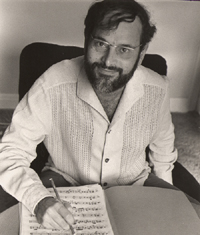

André making corrections (1975)

(2nd, 3rd, 4th Performances)

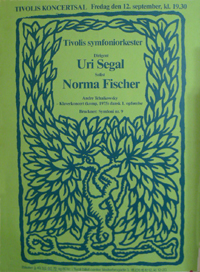

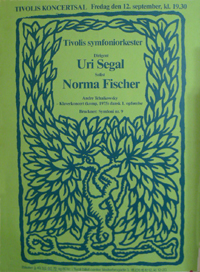

Copenhagen

Concert Poster

Norma Fisher (1986)

(5th Performance)

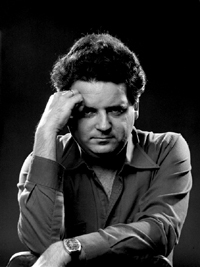

Uri Segal (Conductor)

Copenhagen, Denmark

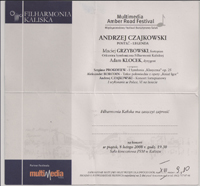

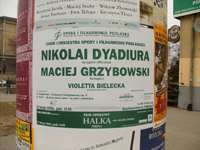

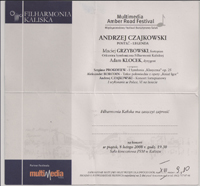

Kalisz Concert

Poster

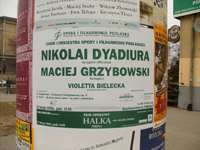

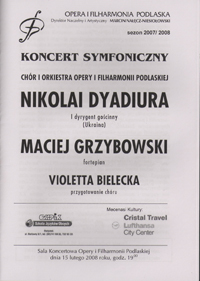

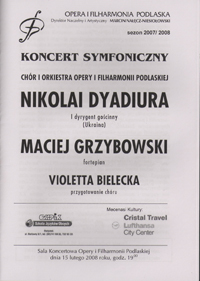

Bialystok Concert Poster

Maciej Grzybowski (2008, 2013)

(6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th

Performances)

Adam Klocek

(Conductor)

Kalisz, Poland

Nikolai

Dyadiura (Conductor)

Bialystok, Poland

Piotr

Wajrak (Conductor)

Lublin, Poland

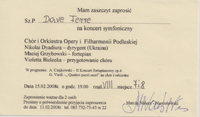

(right to

left) Maciej Grzybowski, Dave Ferré, Halinka Janowska, Aleksander

Laskowski, and Joanna Fidos.

Bialystok, Poland

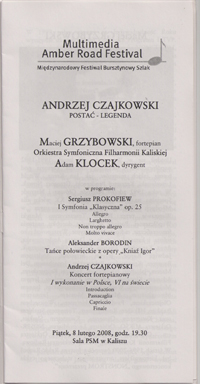

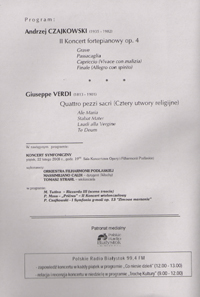

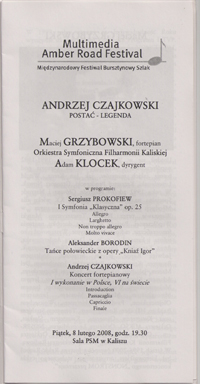

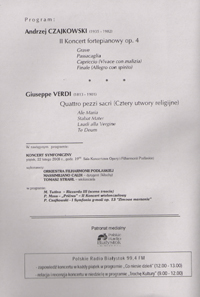

Kalisz,

Poland, Program

Kalisz,

Poland, Ticket

Kalisz,

Poland, Concert Hall

Bialystok,

Poland, Program

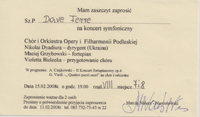

Bialystok,

Poland, Ticket

Marcin Nalecz-Niesiolowski

Artistic Director

Bialystok,

Poland, Concert Hall

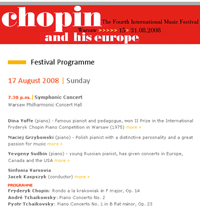

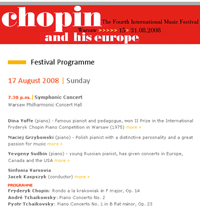

Warsaw Philharmonic

Hall

August 17,

2008 Program

Maciej Grzybowski

- Pianist

August 17, 2008 Concert

Maciej Grzybowski

- Pianist

August 17, 2008 Concert

Maciej Grzybowski

- Pianist

August 17, 2008 Concert

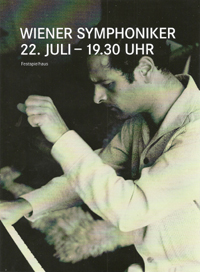

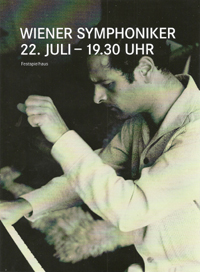

Poster Artwork for July 22, 2013 Performance

Maciej Grzybowski - Pianist

July 22, 2013 Concert

Maciej Grzybowski - Pianist (rehearsal)

July 22, 2013 Concert

Paul Daniel -

Conductor

July 22, 2013 Concert

Program Pages from July 22, 2013 Concert

Dorota Szwarcman

Music Critic for Polityka

(Polish newsmagazine)

|

Piano

Concerto (1966-1971) - Opus 4

This

webpage provides information about the André Tchaikowsky Piano

Concerto - Opus 4. First are music links and then text that lists all

known details regarding this composition, including performances to

date, plus text about the concerto from the book, The Other Tchaikowsky

- A Biographical Sketch of André Tchaikowsky.

(2017)

Piano Concerto, Opus 4 / Lublin Philharmonic

As part of their regular concert season, the Lublin (Poland) Philharmonic

included the Andrzej Czajkowski Piano Concerto Opus 4, which was performed

on September 29, 2017 with performers Maciej

Grzybowski, piano, and Piotr

Wajrak, conductor. This performance was recorded and appears on

YouTube

and Vimeo.

There is also an audio-only recording (see below).

Study

in Contrast (Audio Program)

From a radio program, a Study in Contrast, hear pianists

David Owen Norris and Radu Lupu, plus John Schofield of Josef Weinberger

Music Publishers, discuss the André Tchaikowsky Piano Concerto

Opus 4. Use the following mp3 link: study_in_contrasts_opus_4.mp3

or the player below.

For the

entire Study in Contrast program, see the Miscellaneous

button.

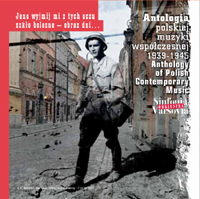

Second

CD Recording of Opus 4 (2014)

Sinfonia Varsovia released a triple-CD anthology of Polish contemporary

music from 1939-1945. The release notes describe the intent: "A

triple album of Polish music associated with World War II is the first

anthology of its kind in Poland. The core of the material on these 3

CDs consists of five works composed in Poland under the German occupation,

while two were written by Polish composers abroad." Click

Here to read more in English; Click

Here to read more in Polish. Note that is is not a commercial release

and is listed as Not For Sale, however, this does show up on websites

such as www.discogs.com.

The Piano

Concerto (1966-1971) Opus 4 appears on CD disc 3. This performance is

on this webpage (Click Here) and features the Sinfonia

Varsovia conducted by Jacek Kaspszyk, with pianist Majiej Grzybowski.

Images from the CD disc 3 appear below. For a PDF from the CD booklet

related to Opus 4, Click

Here (in English). Click

Here for an online version of the booklet (English and Polish).

For a newspaper review, Click

Here (in Polish).

UPDATE

- This box set is now available for purchase (as individual volumes)

as released by Warner Classics - Poland. To purchase this Volume 3,

Click

Here. Warner Classics also posted this recording of the the Opus

4 piano concerto on YouTube:

This is

also available on Spotify. Click

Here (Spotify login and account required).

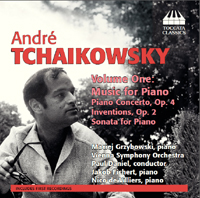

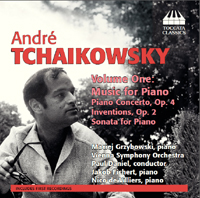

First

CD Recording of Opus 4 (2013)

Toccata Classics released CD TOCC0204 on November 1, 2013, the first

commercial recording dedicated entirely to the compositions of André

Tchaikowsky. Included are the Sonata

for Piano (1958), featuring pianist Nico de Villiers, the

Inventions Opus 2 (1961–62), played by pianist Jakob Fichert,

and the Piano Concerto

Opus 4 played by pianist Maciej

Grzybowski with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul

Daniel.

CD

Cover features a

photograph of André

Tchaikowsky from c. 1966

(André Tchaikowsky Estate)

|

Performers

and contributors (left to right) Jakob Fichert, Anastasia Belina-Johnson,

Nico de Villiers, and Mark Rogers (recording engineer for the

Toccata Classics CD).

|

Links

related to the Toccata Classics CD TOCC0204:

|

The

2013 Bregenz Festival

The centerpiece of the 2013 Bregenz Festival was the world premiere

of André's opera, The Merchant of Venice. Coupled with

the opera performances (there were three), there were "Music and

Poetry" concerts featuring The

Inventions Opus 2, Seven

Sonnets of Shakespeare, String

Quartet No. 2, Arioso

e Fuga per Clarinetto Solo, Trio

Notturno Op. 6, and Tango

and Mazurka (from Six Dances for Piano). Finally, a symphonic concert

featuring the Piano Concerto Opus 4, played brilliantly by Maciej Grzybowski.

Music/MP3

While only one professional recording is available for the Piano Concerto

Opus 4, concert recordings have been made of performances by Radu Lupu

(1975), André Tchaikowsky (1978), Norma Fisher (1986), and Maciej

Grzybowski (2008) (2013), which are listed below as *.mp3 files. Since

the concerto is played without pause between movements, the complete

*.mp3 may offer the best presentation.

Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra

London, England

28 October 1975

Radu Lupu - Piano

Uri Segal - Conducting

00_r_lupu_opus_4_complete.mp3

01_r_lupu_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt.mp3

02_r_lupu_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt.mp3

03_r_lupu_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt.mp3

04_r_lupu_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt.mp3

Irish National

Orchestra

Dublin, Ireland

1 October 1978

André Tchaikowsky - Piano

Albert Rosen - Conducting

00_a_czajkowski_opus_4_complete.mp3

01_a_czajkowski_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt.mp3

02_a_czajkowski_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt.mp3

03_a_czajkowski_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt.mp3

04_a_czajkowski_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt.mp3

Tivoli

Summer Orchestra

Copenhagen, Denmark

12 September 1986

Norma Fisher - Piano

Uri Segal - Conducting

00_n_fisher_opus_4_complete.mp3

01_n_fisher_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt.mp3

02_n_fisher_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt.mp3

03_n_fisher_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt.mp3

04_n_fisher_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt.mp3

|

|

This

performance is on YouTube. Click

Here (opens new window) |

Sinfonia Varsovia

Warsaw, Poland

17 August 2008

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Jacek Kaspszyk - Conducting

00_m_grzybowski_opus_4_complete.mp3

01_m_grzybowski_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt.mp3

02_m_grzybowski_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt.mp3

03_m_grzybowski_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt.mp3

04_m_grzybowski_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt.mp3

Vienna

Symphony Orchestra

Bregenz, Austria

22 July 2013

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Paul Daniel - Conducting

00_m_grzybowski_opus_4_complete2.mp3

01_m_grzybowski_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt2.mp3

02_m_grzybowski_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt2.mp3

03_m_grzybowski_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt2.mp3

04_m_grzybowski_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt2.mp3

Lublin

Philharmonic Orchestra

Lublin, Poland

29 September, 2017

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Piotr Wajrak - Conducting

lublin_opus_4_complete.mp3

lublin_opus_4_introduction_1st_mvmt.mp3

lublin_opus_4_passacaglia_1st_mvmt.mp3

lublin_opus_4_capriccio_2nd_mvmt.mp3

lublin_opus_4_finale_3rd_mvmt.mp3

|

|

This

performance is on YouTube. Click

Here (opens new window) |

Performances

The following is a list of the performances of the Piano Concerto -

Opus 4:

1.

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

London, England

28 October 1975

Radu Lupu - Piano

Uri Segal - Conducting

2.

Irish National Orchestra

Dublin, Ireland

1 October 1978

André Tchaikowsky - Piano

Albert Rosen - Conducting

3.

Irish National Orchestra

Cork, Ireland

2 October 1978

André Tchaikowsky - Piano

Albert Rosen - Conducting

4.

Hagen Symphony Orchestra

Hagen, Germany

17 November 1981

André Tchaikowsky - Piano

Yoram David - Conducting

5.

Tivoli Summer Orchestra

Copenhagen, Denmark

12 September 1986

Norma Fisher - Piano

Uri Segal - Conducting

6.

Orkiestra Symfoniczna Filharmonii Kaliskiej

Kalisz, Poland

8 February 2008

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Adam Klocek – Conducting

7.

Podlasie Opera and Philharmonic

Bialystok, Poland

15 February 2008

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Nikolai Dyadiura - Conducting

8.

Sinfonia Varsovia

Warsaw, Poland

17 August 2008

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Jacek Kaspszyk - Conducting

9.

Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Bregenz, Austria

22 July 2013

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Paul Daniel - Conducting

10. Lublin

Philharmonic Orchestra

Lublin, Poland

29 September 2017

Maciej Grzybowski – Piano

Piotr Wajrak -Conductor

Music

Publisher

This

work is

published by Josef

Weinberger and appears in their catalog of André Tchaikowsky

published works. Click Here

for a PDF copy of the André Tchaikowsky Weinberger catalog.

From

the biography The

Other Tchaikowsky

On August

24, 1971, André was scheduled to play the Goldberg Variations

at Albert Hall Promenade concert. The music critic for the Arts Guardian,

Gerald Larner, asked André for an interview. André thought

Larner one of the better music critics and granted the interview. On

the day of the concert, the interview was published:

Tchaikowsky

Mark Two

I came

across André Tchaikowsky in the street, humming to himself,

his head bobbing in time not with his feet but with the imagined music,

his fingers drumming on the imagined keyboard. So I asked him what

he was playing. "Oh, I'm writing a piano concerto. One movement

is not finished yet." When it is ready he will play it, of course,

but he would rather not give the first performance: "I would

get so nervous."

He gets

very nervous, anyway, about playing in public. "Sometimes I wish

I could drop dead before a concert." But he would never give

it up. If composition is, as he said, "what makes me tick,"

playing the piano is what makes him tock. Even if he could earn a

living as a full-time composer, he would still play the piano: "I

couldn't live without it." Not that he does make money out of

writing music. "I have not made a penny out of it, and I don't

think I ever will."

"Who

plays it?" I asked. "Practically nobody", he said.

But Gervase de Peyer has played his Clarinet Sonata (published by

Weinberger), the Lindsay Quartet will perform his String Quartet,

and Margaret Cable has sung his cycle of Seven Shakespeare Sonnets.

He has also written a violin concerto and Novello is about to publish

some piano pieces called The Inventions.

Most

young soloists could not find time for composition even if they had

the inclination. "Writing is a pretty obsessive occupation. I

don't do it when I am on tour. It is too demanding." So, in order

to tick, he takes a few months off every year, usually June and July.

A couple of years ago it was three winter months in the mid-season,

which is professionally unheard of. In order to make sure that he

is tocking properly, he also takes time off to visit "an old

lady in the Lake District" who apparently has a "fantastic

ear." She listens to his playing and, without concerning herself

with interpretation, picks holes in his technique. "She treats

me as if I were six. She's very bad for my self-confidence."

Obviously,

André Tchaikowsky is no ordinary career pianist. His reputation

of being "difficult" still lingers on. This has only partly

to do with his musical principles - that he won't play works he is

not "crazy about," like Grieg, Tchaikovsky, and Rachmaninoff

concertos, which are "corny." He has doubts even about the

"Emperor" and Bartok's Third, though Bartok has been one

of the major influences on his own music. Bartok's Second is "just

too difficult. My arms would drop off." But he plays the Schumann

and Beethoven's Third and Fourth, which are his favourites outside

of Mozart. "Mozart comes first every time. Most people would

agree that humanity and perfection are mutually exclusive, but the

exception is Mozart."

Nor is

his reputation for being difficult due to the occasional awkward encounter

with conductors. "I don't get on with grand old people,"

he admits, and prefers to work with young ones. "Old conductors

are much bossier and less flexible," particularly some senior

German ones who apparently like to maintain a military discipline

and expect him to salute and "Jawohl" rather than discuss

the interpretation. His fingers drummed on the keyboard again, and

the baldish head bobbed in time.

Eventually,

before he came to settle in this country, "everyone was sick

to the teeth with me. They thought I played the piano rather well

but they found me insufferable.” But he finds that it is only

a "false situation" which brings out the worst in him. Even

in England, which he regards as a "supremely civilised country

-- the first in which a central-European refugee like me could feel

really safe," he had a difficult time at first. He had so little

work between 1960 and 1962 (having got on the wrong side of his manager)

that he had to borrow money from his teacher, Stefan Askenase.

Now,

however, he seems quite happy. Certainly, I found him very polite

and unusually modest, with a cheerful sense of humour. The more he

feels at home, the better the sense of humour works. New Zealand,

for example, he regards as "Arcadia, so innocent, so unspoilt,

no snobs, no rat race." And it was in New Zealand, on a recent

tour with Christopher Seaman, that, for an encore, Tchaikowsky conducted

the orchestra and Seaman played the piano. The orchestra was as surprised

as the audience: "For heaven's sake", André told

the orchestra, "don't pay any attention to me."

Another

place where he is happy, and popular as a teacher, is the summer school

at Dartington. "Where else can you play to an audience two-thirds

of which you are sexually attracted to?" I said I didn't know.

He said that once when he could not be at Dartington he sent a postcard

saying simply, "I love you. Will you marry me?" They pinned

it to the notice board. He was there again this summer.

Most of

June, July, September, October, and December of 1971 was kept free of

concerts. André was bearing down on completing a composition

started in 1966.

After many

starts and stops, writings and rewritings, the Piano Concerto (1966-1971)

was completed in December 1971. There were occasional references to

the concerto in correspondence during the years, but things really didn't

start to sound conclusive until 1970. In a letter to Halina Wahlmann-Janowska

on November 4, 1970, André wrote:

Dear

Halinka,

The famous

piano concerto is not ready yet. I should call it, "The Eternal

Song," but I think it's turning out quite well. So far, four

people have seen it: Stefan Askenase, Stephen Bishop [Kovacevich],

Hans Keller, and George Lyward (the psychologist that I've told you

so much about). Everyone was very impressed. I was most happy with

Lyward's reactions because he's not a professional musician and he

reacts instinctively. It appears that my music can influence someone

who doesn't go into the particulars of musicological analysis, that

normal human sensitivity is quite enough.

Yours,

André

On occasion,

André would visit the Harrison/Parrott office in London. One

reason for his visits was to use their photocopy machine to make copies

of his compositions. On one visit in 1970, with a great pile of papers

tucked under his arm, André ran into another Harrison/Parrott

artist, pianist Radu Lupu. Lupu, a man of few words, remembers his brief

conversation with André:

Lupu:

What are these papers?

André: My piano concerto.

Lupu: Oh, I will play it.

André: You do not know it.

Lupu: Tell me then.

André: It has a slow introduction...

Lupu: I adore slow introductions.

André

couldn't believe his good fortune. He admired Lupu's piano playing and

his willingness to play the concerto would practically guarantee a performance.

However, it wasn't quite that easy. After more than a year of trying,

Terry Harrison found no orchestra interested in this new work, partly

because it was very difficult and would require extra rehearsals. In

July 1973, Terry Harrison wrote to Hans Keller at the BBC asking if

they might arrange a first performance. Hans sent Terry to the planner

at Royal Festival Hall, and, by November 1974, a date had been set.

The concerto would be played in the Royal Festival Hall by the Royal

Philharmonic, conducted by Uri Segal, and the pianist, of course, would

be Radu Lupu. The date was October 28, 1975.

What Radu

Lupu didn't know was that the concerto was terribly difficult and would

take him nearly six months to learn. Radu Lupu:

"André

came to my house about two weeks before the performance. He practically

moved in with me and we played day in and day out. It was wonderful

help. He was the orchestra on one piano, and I was soloist on the

other piano. André was so patient with me, so incredibly patient

and nice to me. The concerto was his child, and he was like a father

to the child. I'm not sorry now, but it was a lot of work and I swore

more than a few times. Uri came by to listen and to 'conduct.' André

and Uri knew each other and were already good acquaintances, but it

took a while for them to warm up to each other. I was very nervous

before the performance. I was green with nervousness. The concerto

is very difficult, so hard to play. I used the music at the concert,

but I had it memorized and only looked at it maybe a few times. I

never argued with André. I knew there were some people you

didn't want to be on the wrong side of, and André was one of

them."

To Halina

Wahlmann-Janowska, André wrote on October 14, 1975, less than

two weeks before the premiere performance:

My darling,

crazy, and luckily incurable genius,

On the

28th of October the first performance of my piano concerto is taking

place in London. Radu Lupu is playing and Uri Segal is conducting

the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The trouble is that they only have

time for one rehearsal, the day before the concert, and the music

is incredibly complex. On the day of the concert, they're going to

have a run-through and that's it. To make things easier for Uri, I've

spent about 100 hours correcting orchestral parts, which were full

of mistakes. But the concerto is so difficult that it may simply turn

out to be unplayable. What am I going to do if the day before the

concert the orchestra announces that it simply cannot be played? Everybody

is nervous: Radu, who plays the piano part brilliantly, Uri, the orchestra,

my agent, my publisher of the music score, and me.

Yours,

André

The concerto

was dedicated to George A. Lyward in the original manuscript, but to

pianist Radu Lupu in the published version. The change of dedication

may have something to so with the enormous amount of work required of

Radu to learn the concerto.

The concert

itself was a spectacular event in the world of pianism. Here was one

of their own, who had written a concerto, and it was to receive a first

performance by someone they regarded as one of the world's leading pianists.

Virtually every pianist in Europe who could make the concert was there.

Someone said that if Royal Festival Hall had collapsed that night, half

of the world's greatest pianists would have perished.

All the

London newspapers reviewed the concert. The reviewers were unaware of

André's earlier piano concerto (1956-1957), hence, they called

this his concerto No.1, or his first concerto. Joan Chissell of The

Times reported:

RPO

/ Segal

In the

nineteenth century, and even the early twentieth, too, there would

have been nothing unusual about going to hear a new piano concerto

composed by a well-known concert pianist. In fact, it would have been

far more strange to encounter a performer of note not given to spare-time

composing. In our highly specialised world of today, things are different.

So last night's premiere of the piano concerto No.1, written by the

eminent Polish-born pianist André Tchaikowsky, was an event.

Perhaps because he was anxious to stress the growing ascendancy of

the composer in himself over the pianist, Mr. Tchaikowsky did not

play it. The soloist with the RPO under Uri Segal was Radu Lupu.

The work

is in three continuous, interlinked movements lasting for about 27

minutes. No one but a virtuoso of the first order could tackle the

solo part. Yet not a note is there for mere display. Piano and orchestra

are as closely integrated in a disciplined, purposeful argument as

in the concertos of Brahms. Although, in his introductory note, the

composer let us into formal secrets (a passacaglia to begin with,

followed by a scherzo-like Capriccio and a Finale combining fugue

and sonata), there was little about underlying 'programme.' Yet the

work is dramatic and intense enough, in an often strangely ominous,

disquieting way, to suggest very strong extra-musical motivation.

There are moments of melancholy just as deep and tortured as in Berg

opus 1 [piano sonata]. Not for nothing is the glinting central Capriccio

headed "vivace con malizia": it is a 'danse macabre' ending

in catastrophic climax. Even the Finale, at first suggesting emotional

order won by mental discipline, eventually explodes in vehemence before

the sad, retrospective cadenza (picking up threads from the opening

Passacaglia) and the hammered homecoming.

If nearer

in spirit to composers of the Berg-Bartok era than the avant-garde,

Tchaikowsky still speaks urgently enough in this work to make his

idiom sound personal. Much of it is also strikingly conceived as sound,

with telling contrasts of splintered glass and glassy calm in the

keyboard part. The Capriccio is a spine-chilling tour de force for

the orchestra too. In view of fantastic difficulties, the performance

held together remarkably well, with Radu Lupu surpassing himself in

virtuosity and commitment.

Joan Chissell's

review (above) was highly influenced by Judy Arnold, André's

former Personal Representative. Judy remembers:

As far

as Joan Chissell's review in The Times is concerned, I have

to have a laugh. Joan was a close friend. She utterly hated having

to give in her copy immediately following a performance. She was much

happier as a writer having her own time and space in which to develop

her ideas. She was utterly not acquainted with any modern music, and

didn't at all like the idea that she had been given the assignment

of a new piece of music to review, and she phoned me up and asked

me what she should say about the concerto before attending the performance.

I, of course, didn't know anything about it, as I hadn't heard it,

but I knew André's style of writing, which, at the time (and

still) seemed most decidedly not-modern (if I can put it like that).

There is of course nothing wrong in that. Thus, Joan's views on the

concerto have got quite a lot of me in them.

Max Loppert

wrote for the Financial Times:

André

Tchaikowsky's Concerto

The long

and glorious tradition of piano concertos written by renowned virtuosi

was continued last night -- honourably, if not remarkably -- in the

first performance of André Tchaikowsky's first essay in the

form. Mr. Tchaikowsky, who might have been expected to produce for

his own use one of those whizz-bang thunderers guaranteed to win a

certain kind of immediate success, has instead composed for Radu Lupu

a concerto that honestly attempts to set out a disciplined and rigorously

conceived musical argument, in which all extraneous piano fireworks

have been sternly abjured.

It was,

from the outset, rather impressive to encounter music of this kind

concerned with "strict construction" (the composer's phrase),

made with clean-cut neo-classical materials purposeful and determined

(the possibly unhelpful contrast with the bombast of David Morgan's

new piece on Sunday was encouraged by the presence of the same orchestra,

the Royal Philharmonic). At best, in the central Capriccio movement,

something of an individual personality, quicksilver, angular and hard-edged,

can be detected through the Stravinskyian cut-and-thrust, the late-Prokofiev

flourishes and moto perpetuo passagework.

Elsewhere,

in the Introduction and Passacaglia, but more so in the Finale, brandishing

its fugue, sonata, and toccata, a slight greyness threatens to seep

out from the basic material, a want of burning organic energy to be

revealed behind the formal gestures. It will be interesting to hear

the work again, with an orchestra and conductor more firmly in possession

of the shifting rhythmic patterning than were the RPO and Uri Segal.

An important novelty that cannot be undervalued in the concerto is

the provision of a new performance personality for Radu Lupu, one

much spikier and less self-possessed than he has so far disclosed

in London, and rewarding to meet. On this form, forward-thrusting

as well as dreamy-toned, a whole range of greater 20th-century piano

concertos awaits his attention.

Edward

Greenfield wrote for the Arts Guardian:

RPO

/ Segal

There

were some, I imagine, who came to this Festival Hall concert puzzled

that the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra were offering the world premiere

of Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto. It was of course quite different

music from the celebrated B-flat minor of Peter Ilych, for the pianist

André Tchaikovsky is also a composer and has delivered himself

of a piano concerto. For this first performance he had the rare restraint

to sit in the audience and get a distinguished colleague, Radu Lupu,

to play the solo part instead of himself.

"I

made a determined effort not to write a 'prima donna's favourite,'"

Mr. Tchaikovsky explained in his programme note, and, for the first

five minutes, that seemed the understatement of the year. Like the

B-flat minor concerto, the new Tchaikovsky first starts with an introduction,

but in the composer's own words, 'it is slow and austere,' and the

piano for three whole minutes never gets a look-in, while the thematic

material for the whole work is grittily outlined. After that, flamboyance

still rejected utterly, the pianist enters with a long and ruminative

solo, which sets the pattern of wrong-note romanticism in gently flowing

lines.

As a

virtuoso, Mr. Tchaikovsky is an unashamedly flamboyant musician, but,

whether to compensate or in genuine revelation of his inner self,

much of this work takes quite the opposite course. Even when the first

movement Passacaglia really gets going, there is little display. But

then, with the Capriccio second movement (Goya's grotesque Capriccios

implied as an inspiration), and even more in the sonata-fugue Finale,

the composer begins to enjoy himself. The energetic last movement

may be the most obviously derivative of the three, but it is also

the most memorable.

Radu

Lupu, dedicatee as well as soloist, was the most persuasive of advocates,

but the orchestral accompaniment (including much solo string work

but with only 16 violins generally working in unison and no second

violin section) was difficult enough to present the RPO and Uri Segal

as conductor with serious problems. At least such passages as the

desolate end of the Passacaglia and the toccata-like coda of the Finale

suggested that with more time for preparation, the whole structure

would hang together better.

The piano

concerto was one of the few exceptions to André's rule of not

playing his own compositions in public. André never played his

"The Inventions" in public, or his clarinet sonata, but his

concerto was different. If Radu Lupu had been indisposed on the October

28, 1975, for the piano concerto, André had already memorized

the work and could have stepped in at the last minute.

Terry Harrison

had hopes for future performances of the piano concerto after the world

premiere. In a December 1975 letter, Terry wrote to André's German

manager:

Dear

Hans Ulrich,

Recently

the world premiere of his first orchestral work took place. This was

a piano concerto, played by Radu Lupu. Incidentally, the success was

very big and there are going to be two repeat performances, including

a London performance in the 1977 Proms. There is also interest abroad

-- I think it may be done in Stuttgart -- Previn is interested in

doing it with Radu in Pittsburg, and Foster is interested in doing

it in Houston.

In a January

1976 letter, Terry tried to interest Christopher Seaman and his Glasgow

Orchestra, but Christopher had to refuse due to inability to give the

concerto proper rehearsal time. Terry wrote letters literally for years

to BBC facilities, orchestras, and conductors, trying to find a second

performance. By 1977, Radu withdrew his selection as a soloist as the

concerto had now slipped from his fingers. Radu, and others, so thought

it a shame that a second performance was not forthcoming. Terry continued

his efforts, this time promoting André as the soloist.

Finally,

the Irish National Orchestra, conducted by Albert Rosen scheduled two

performances, one in Dublin, on October 1, 1978, and the second in Cork,

on October 2,1978. The recordings from these performances are only a

few of the official recordings ever made of the concerto. The performance

was reviewed by Robert Johnson of the Irish Press:

André

Tchaikowsky was soloist in his own piano concerto (first performed

in 1975). It is in three movements and very modem in style if a trifle

episodic, and the inner movement is full of delicate and exciting

ideas, particularly the percussion effects. Like many modern works

it needs to be heard again, exciting as it was.

Terry continued

to push for additional performances. Copenhagen had agreed to schedule

the work, and finally, the BBC agreed to make a recording for a radio

broadcast. The orchestra in Hagen, Germany scheduled the concerto for

November 17, 1981, and again André was the soloist, with conductor

Yoram David. The critical review in the Westfalenpost:

First

Performance at City Hall

A very

memorable event occurred last night in Hagen with a concerto performance

at the City Hall. The conductor, Yoram David, presented a 1971 composition

for piano and orchestra written by André Tchaikowsky, with

the composer personally at the piano. This was the first German performance.

The concerto

is dedicated to the famous pianist, Radu Lupu, who played the world

premiere in 1975 at the London Royal Festival Hall. The concerto was

presented again in Ireland, in 1978. Yoram David was excellent and

the concerto is surely the best since Brahms.

A critical

review in the Westfalische Rundschau (No. 270) reported:

German

First Performance - Tchaikowsky

The fourth

Hagen symphony concert introduced, as a German first performance,

the André Tchaikowsky piano concerto. The first performance

was given at the Royal Festival Hall in London in 1975. It is a masterpiece

of composition.

André

Tchaikowsky (age 46), especially appreciated as a Mozart virtuoso

all over the world, played the piano part at the Hagen City Hall concert

himself. Is the concerto calculated such that the piano part is dominant?

André Tchaikowsky: "This is what I've tried to avoid.

The instruments are introduced in groups and separately. The work

is so polyphonic as to make great demands on every member of the orchestra."

André

Tchaikowsky, who appeared very successfully as a soloist with the

Hagen Symphony orchestra in 1964, played his unique concerto only

twice before, both times in Ireland. Yoram David, the conductor of

this event, says: "This concerto for piano and orchestra is a

phenomenally good work, tremendously crafted and is without a superfluous

note."

Another

reviewer in the Westfalische Rundschau (No. 271) wrote:

Tchaikowsky

Concerto Well Received

The audience

at the fourth symphony concert heard the German premiere of the concerto

for piano and orchestra by André Tchaikowsky, which was received

with great applause. World experts of the piano raved about the first

performance of this famous composition at the world premiere at the

Royal Festival Hall in 1975.

Yoram

David and the orchestra rehearsed the concerto in a short time. It

is in three movements of various themes which were worked in a logical

and consequential manner. After the performance, Yoram David and André

Tchaikowsky offered an opportunity to discuss the work at an interview

session. [André's fluent German amazed Yoram David.]

The Hagen

orchestra gave the concert an excellent interpretation, including

many instruments not usually heard. The theme was worked out intelligently

and well considered, as Yoram David obviously enjoys the composition,

giving it precise tempi and excellent sound levels.

The concerto

was scheduled to be recorded by the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Albert Rosen, with André as soloist, on March 2

and 3, 1982. Unfortunately, André was ill at the time, and the

session had to be canceled. The Copenhagen performance promised by André's

good friend Lars Grunth took place but not with André as soloist.

The soloist was British pianist Norma Fisher. Norma had also given the

first complete public performance of André's "The Inventions."

The Copenhagen performance was on September 12, 1986, with the Tivoli

Summer Orchestra, conducted by Uri Segal. Music critic, Jan Jacoby,

wrote of the Copenhagen performance in the Politiken:

Norma

Fisher with Tivoli Symphony Orchestra under Uri Segal

If it

was the horror of having Bruckner's last symphony spoiled by a modernistic

thriller before the intermission that made people come too sparsely

to Tivoli's last, symphony concert this season, then it was due to

a misunderstanding. For André Tchaikowsky's Piano Concerto

is only modern from a chronological point of view.

Most

noticeable was the stylistic reference, which has very little to do

with the 1970s. Tchaikowsky had his ears well tuned to Central Europe

around the first World War, a place between Mahler and Berg, with

the rhythmic twentieth century modernism in view. Norma Fisher gave

a technically impressive and strongly committed performance.

Critic

Hans Voigt wrote of the Copenhagen performance in the Berlingske

Tidende:

Individual

Against Society

"Writing

music is just another way of telling a story," pianist André

Tchaikowsky, the pianist and composer, once said during a visit to

Norway. He also revealed that it was Peggy Ashcroft's acting in Ibsen's

"Rosmersholm" that had given him the inspiration for his

piano concerto. Ibsen's description of an uncompromising hero, an

individual against society, could also be seen as the lone piano against

the enormous forces of the violent and complex orchestra.

But what

comes through even without this background knowledge is an impressive

work with much artistic and constructive strength. The concerto is

a virtuoso work, without being overwhelmingly so, the whole musical

development being taken from the opening slow orchestral introduction

and culminating in the exceptional final closing theme.

The excellent

Norma Fisher played the concerto with remarkable skill, where soloistic

bravura, radiance, gentle strength and the authority of personality

were united effectively.

The two

Polish performances in February, 2008, featuring Maciej Grzybowski at

the piano were very exciting and each concert hall in Kalisz and Bialystok

were full to the last seat. Maciej rose to the difficult task at hand.

In a previous 2006 concert featuring the music of Andrzej Czajkowski,

the Warsaw Voice had this to say about Maciej:

Czajkowski

Rediscovered

Olsztyn

and Kielce will soon host two interesting concerts dedicated to the

music of Andrzej Czajkowski. Last November marked the 70th birthday

of the late outstanding pianist, whose achievement as a composer remains

virtually unknown.

Maciej

Grzybowski, one of the most interesting Polish pianists around, has

decided to change this state of affairs. Fascinated with Czajkowski's

music, he tries to feature Czajkowski's works into his own performances.

According to Grzybowski, Czajkowski is "the greatest Polish composer

after Chopin, Szymanowski and Lutoslawski, and next to Penderecki

and Szymanski." "Here is an artist of phenomenal technique,

extraordinary imagination, an amazing sense of musical drama, no less

than brilliant intuition unmistakably leading him towards the 'yet

undiscovered,' an extremely rare sensitivity to sound-its color and

context-and harmonics; a master of declamation and structure showing

a 'flair for the dramatic,'" says Grzybowski.

At the

Olsztyn Philharmonic March 24 and the Swietokrzyska Philharmonic in

Kielce April 3, Grzybowski will present a program of Czajkowski's

works, accompanied by excellent musicians: Urszula Kryger-vocal, Krzysztof

Zbijowski-clarinet, Marcin Suszycki-violin, and Karol Marianowski-cello.

The program includes Sonata for Clarinet and Piano (1959), Inventions

for Piano (1961/62) and Seven Sonnets by Shakespeare for Voice and

Piano (1967).

Czajkowski

was born Nov. 1, 1935 in Warsaw. He studied in Poland, France and

Belgium. In 1955, he garnered acclaim as the youngest laureate of

the Frederic Chopin Competition. In 1956, he received the Third Prize

at the Queen Elizabeth Competition in Brussels. In the same year,

he left Poland to settle in England. He was a very successful pianist,

giving 500 recitals and concerts over three years, as well as making

many recordings. Later he devoted himself to composition. He died

in 1982 in Oxford.

A review

of Maciej Grzybowski's concerto performance in Kalisz on 8 February

2008 was published by the Polska Agencja Prasowa (PAP). (Click

here for the Polish version as a PDF file.)

First

Time in Poland

Piano

Concerto by Andrzej Czajkowski

Kalisz

(PAP) - Pianist Maciej Grzybowski was rewarded with a standing ovation

after his performance Friday evening in Kalisz of the piano concerto

of Andrzej Czajkowski (1935-1982).

This

music by Andrzej Czajkowski was performed for the first time in Poland

and for only the sixth time in the world. The Kalisz Philharmonic

Orchestra was conducted by the Director Adam Klocek. In the first

portion of the concert, music lovers heard Sergei Prokofiev’s

Symphony No 1 in D major "Classical Symphony," Op 25, which

was followed by a dance from Prince Igor, an opera by Aleksandr

Borodin.

Friday's

concert was one of the biggest events of the current artistic season

in Kalisz. There was not one empty seat in the concert hall, located

in the John Paul II Plaza. After the concerto performance, the audience

was hoping for more but Director Klocek explained that due to the

demands that the concerto placed on the pianist, that Grzybowski would

be unable to honor the request for an encore. According to the Director,

the concerto was the most difficult piece the orchestra has ever performed.

The occupants in the box seats were stating that the concerto fine

performance would undoubtedly go down in history.

They

also underlined that Czajkowski’s music was a reflection of his

difficult life. As a Jewish child during the second world war he was

hidden in a closet. Later on he wanted to catch up with his lost years

and - often by playing and later by composing. "His music reflects

all of his life," - people were saying.

Czajkowski’s

Piano Concerto was first performed by Radu Lupu and Uri Segal at the

Royal Festival Hall in London in 1975, and was declared by critics

at that time as the best piano concerto since the time of Bartok.

A special guest at the Kalisz concert was music lover, biographer

of Andrzej Czajkowski, and author of the Internet page about him -

American David Ferre.

According

to Adam Klocek, the concerto concert was a true Polish event. Czajkowski

was a pianist playing in the largest concert halls of the world. He

also recorded many records for well known recording companies. The

director mentioned that while he was somewhat forgotten in Poland

he still has many fans.

Czajkowski

was born in Warsaw. From 1945 through 1948 he was taking piano lessons

in Lodz under the instruction of Emma Altberg. Later he studied in

Paris under Lazare-Levy, and next in Sopot and then Warsaw. In 1955

he received eighth place and was the youngest pianist in the Fifth

International Piano Contest held in the name of Fryderyk Chopin. He

also received special acknowledgment from Arthur Rubinstein.

After

his success at the Chopin competition, Czajkowski traveled to Brussels.

Later he performed in Europe, the United States and New Zealand with

the finest orchestras of the world under conductors like André

Cluytens, Karl Bohm, Carl Maria Giulini, and Carlo Zecchi. During

the 1950s and 1960s Czajkowski performed 500 piano recitals with tremendous

success. In 1960 he settled in London. He died in Oxford.

On August

17, 2008, the Piano Concerto was performed again by Maciej Grzybowski

as part of the Chopin

and his Europe Festival in Warsaw, Poland. [Click

Here for a review of an October, 2009 recital by Maciej Grzybowski,

at the Polish Embassy in Washington, D.C. USA.] The following review

for the Polityka newspaper by Dorota Szwarcman appears on her

website.

Andrzej

Czajkowski

Briefly,

from the flames of an outstanding event on Sunday evening at the Chopin

and his Europe Festival...

This

is about the Piano Concerto No. 2 by the composer Andrzej Czajkowski,

who lived in Great Britain for many years as André Tchaikowsky.

The concerto was performed by pianist Maciej Grzybowski who tirelessly

promotes the music of Andrzej Czajkowski, and with the Sinfonia Varsovia

under the baton of Jacek Kaspszyk, who some years ago met Andrzej

Czajkowski in London.

Although

André Tchaikowsky was the hero of the "Hamlet" story

from the book by Hanna Krall, Proof of Existence, this is about

music, about composition. Tchaikowsky was a fantastic and well-known

pianist, but apparently preferred the life of an unknown composer.

In general, composing as a career is not easy, but it is even more

so for Tchaikowsky because his compositions are difficult and require

total commitment from the musicians.

Maciej

Grzybowski is very involved in restoring, and properly placing on

a concert stage, the compositions of André Tchaikowsky. To

this extent, Grzybowski performs Tchaikowsky's music all over the

country and plays songs [Seven Sonnets of Shakespeare], piano pieces

[The Inventions], and chamber works [Trio Notturno, Sonata for Clarinet

and Piano] as well as the Piano Concerto No. 2. I was at a concert

once in Olszytn that was dedicated entirely to compositions by André

Tchaikowsky.

For this

concert, Grzybowski wrote his own program notes and I asked him if

the music is physiological? For me, this is music after the world

war catastrophe, which connects it to works by composers from the

Terezina Concentration Camp, for example, with Gideon Klein and Viktor

Ullmann. Maciej agreed that to a certain extent that - yes - this

is holocaust music. Well, this is subjective. The objective is excellent

musicianship by performer and composer, and it just chokes me up.

For me, it's the piano concerto.

The Piano

Concerto (1966-1971) Opus 4, was published by Josef Weinberger, Ltd.

in 1975; a two-piano reduction by the composer was also published.

|